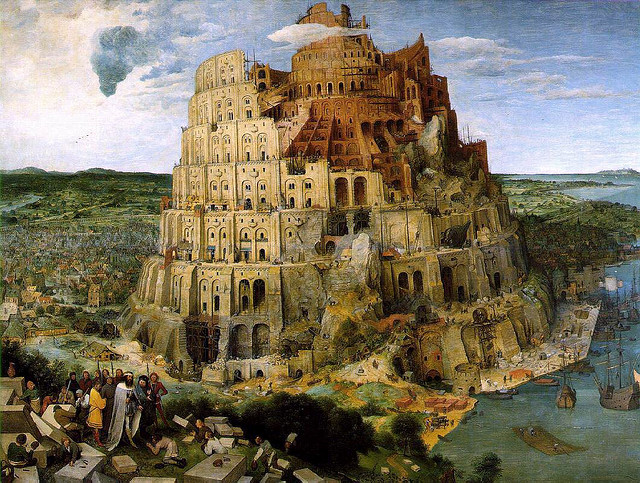

About a year ago I got curious about finance. Money, whatever else it is, is an infrastructure (like a road) enabling economic activities; furthermore, it is a platform (like the Internet), in the sense that it can be reconfigured ad infinitum, and that you can combine finance to make more finance, layer upon layer, just like this blog is made of code sitting on top of a network protocol.

About a year ago I got curious about finance. Money, whatever else it is, is an infrastructure (like a road) enabling economic activities; furthermore, it is a platform (like the Internet), in the sense that it can be reconfigured ad infinitum, and that you can combine finance to make more finance, layer upon layer, just like this blog is made of code sitting on top of a network protocol.

I am doing work on public policy for social innovation, and social innovation has an access to capital problem. Makes sense: social innovators, even though they might generate revenues and even profit, care mostly about producing social benetits. Capital, on the other hand, is out for monetary returns, not social ones. An investiment’s social benefits, even when enlightened investors care about them (when they do they are said to do impact investment), are subordinate to financial returns.

Last week, in London, I had a long chat on this topic with Karl Richter, a young architect turned financier through urban regeneration. He and others have been designing financial instruments for social enterprises and social innovation. For example, a line of work is to bundle two different financial sources: a core of “philantropic capital”, for which social returns are the main concern, and an outer layer of impact capital, looking for market returns on socially responsible investments. Bundling happens in a way that lets philantropic capital carry the loss (or the less-than-market-level returns) if the investments turns sour. In this way, non-philantropist investors are guaranteed; and the benefits of philantropic capital are greatly augmented, because an euro of philantropic capital activates three euro of credit.

This kind of work is important in the context of the fledgling European strategy on social innovation. However, there is a side to this story that no one is looking at, and that’s the emergent consequences of digging new financial channels for this kind of enterprise. History teaches us that financial innovation often has completely unintended consequences, and some of those are truly evil. For example, stock exchange markets were a great idea, because they allow savers to participate to the risk capital of public companies. Since the return on investment depends on profit, risk is shared across shareholders. Since buying and selling shares is cheap and easy, companies can get cheap access to capital and money flows to those firms that invest wisely, securing high returns and low risk. Over time, though, the existence of stock markets transformed the savings and investment landscape. Individual investors keeping part of their saving in blue chips over the long term went extinct: participants in the stock market are now mostly fund managers, continuously redeploying their money as they try to secure a marginally higher rate of return. Unintended consequence #1: top managament’s obsession for the short term of the quarterly result. Unintended consequence #2: stock market bubbles. Both pretty bad.

You see, channeling finance onto social innovation, difficult as it is, is not going to be enough. We need to do it without distorting the incentives that makes social innovators so good at what they do. For this we need a much better understanding of emergence in the social and economic world than we presently have, and we need it now. I have started doing work on this theme with David Lane’s group at the European Centre for Living Technology, and I really hope I can dig out something to contribute.