In the last year, as I took part in a Council of Europe workgroup that tries to make sense of some emergent phenomena in the economy, I got the idea that social innovation is really, really important. Certainly important enough to curve the mental space I inhabit: whatever I do I seem get more and more entangled into it. The latest news – though not the last, I have a feeling – is that the Young Foundation, a British think tank close to the European Commission’s President Barroso and the single most active organization on the social innovation front, has enrolled me for the advisory board of the new Social Innovation Initiative for Europe. The projects’s objective is to create a social innovation community hub that, among other things, will provide input into the design of a new European social innovation fund.

European funds are large scale financial instruments for public policy. They are measured in hundreds of millions of euro, if not billions. Their allocation criteria among and within member states are the object of thorough negotiations, led by the highest ranking European public officials. The Commission does not design new funds every day: clearly, someone at the top thinks this is a very important matter.

From my vantage point as a Council of Europe advisor it is not hard to figure out what’s going on. The representative of the States in our group are worried silly: the welfare state, keystone of the European social model and staple ingredient of the Old Continent’s humanized version of capitalism, is crumbling before an irreversible fiscal crisis. No one believes the current level of public service provision is defensible within the current model. And no, it can’t be put down to ineffective management. We are not talking about Italy or Greece here: the most worried people I talked to come from advanced welfare countries like Austria or Norway, in which the public would never accept a retreat from the current service level – a retreat that, nevertheless, is coming.

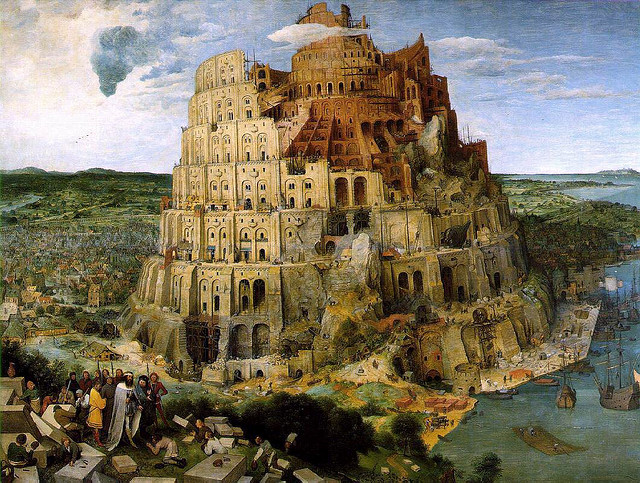

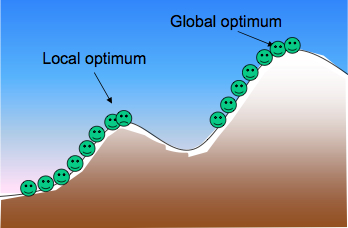

Interestingly, though, no one is talking about privatization. We learned a lesson in the 80s, and that is that privatized public services are not necessarily any cheaper than those directly provided by the State. There are many reasons for this, and an important one is that the private for-profit sector wants to, well, make a profit. And that means high margins: if they are not there, private business is simply not interested. Here’s where social innovators gets to be given a chance; their blend of social economy (i.e. weak orientation to profit) and disruptive innovation borrowed from their Silicon Valley brethren is the only candidate for providing solution to turn public services around the way Wikipedia did with encyclopedia writing, defending the level of service while driving costs way down.

It does not take a genius to figure out where this is going. It leads to public services that are redesigned from the ground up, and that will look nothing like what we are used to. School? YouTube videos (Khan Academy style) instead of teachers in classrooms. Health care? Online fora instead of queing up at your local doctor for most less serious conditions. University? A badge system for informal learning on the open web instead of degrees (the Mozilla Foundation is working on it already). Policy design? Wikicracies instead of professional weberian bureaucracies. It’s safe to predict that the transition to such a scenario will be problematic, and it will imply very many people who are working in the public sector becoming — to put it bluntly — completely useless, because we can’t use what they can do and they can’t do what we need done.

The fund that the European Commission is designing can address at best half the problem; enabling social innovators to rethink radically public services. The other half is to make sure that the social contract holds, and that scared, enraged Europeans do not take to the street to set fire to cars, ATMs or their slightly different-looking neighbours. For this we need a high level political leadership: the present system was conceived by giants like Bismarck (the pension system) and Lord Beveridge (modern welfare). Let’s hope we find comparably enlightened leaders for the current phase.