Makers is a novel, published in 2009 by Canadian science fiction author and Boing Boing co-editor Cory Doctorow. It deals with two entrepreneurs from the DIY scene (think MAKE Magazine, or Wired’s New Industrial Revolution), Perry Gibson and Lester Banks, inventing new things. Their inventions transform the world around them, not so much from a technical as from a social and economic point of view. They give rise to a highly decentralized organization and business model called “New Work” in the fictional context of the novel. I was referred to it by friends in the Italian physical hacking scene, which I started hanging out with in 2008.

Makers is a novel, published in 2009 by Canadian science fiction author and Boing Boing co-editor Cory Doctorow. It deals with two entrepreneurs from the DIY scene (think MAKE Magazine, or Wired’s New Industrial Revolution), Perry Gibson and Lester Banks, inventing new things. Their inventions transform the world around them, not so much from a technical as from a social and economic point of view. They give rise to a highly decentralized organization and business model called “New Work” in the fictional context of the novel. I was referred to it by friends in the Italian physical hacking scene, which I started hanging out with in 2008.

When I first read the book I found it very prophetic, in the way that the best science fiction can be; also, I was stricken by how much of it translated pretty directly into widely accepted economic theory. After musing on it for about a year, I have become a convert (so much that I have participated in Arduino-based projects and started out experimenting with economic policy for makers). At the same time, though – in the context of some research that I am involved with – I have started to ask myself if the “innovation society” we seem to be trying to build (witness the Lisbon Strategy and innumerable policy documents) is indeed sustainable. Increasing quantities of innovation, after all, sort of implies the economy growing at an increasing rate, and this is likely to have straining side effects on the natural environment or even our own human limitations. Does innovation have a dark side? How much of can we take without descending into dystopia?

Doctorow has created a pretty believable fictional economy which seems to be, in some sense, the innovation society we are heading for. So I decided to study it more closely: that is, re-read the book with an economist’s eyes, to zero in on the economics of what’s going on in there.

Schumpeter’s creative destruction

The main economic engine in the world of Makers is Joseph Schumpeter’s theory of creative destruction. It is laid out straight from chapter one by CEO Langdon Kettlewell in the press conference to announce the Kodak-Duracell merger:

Capitalism is eating itself. The market works, and when it works it commodifies or obsoletes everything.

At the end of the press conference, reporter Suzanne Church – who used to be an economic journalist in Detroit, and as such covered the demise of the car ecosystem – muses about being haunted by decay, even in the Silicon Valley, which was supposed to have incorporated failure as just a step on the road to ultimate success:

Now she was back in that old rustbelt funk, with the feeling that she was witness not to a beginning, but to a perpetual ending, a cycle of destruction that would tear down everything solid and reliable in the world.

Commodification and obsolescence, however, should be thought as a feature, not a bug. It is, in fact the way capitalism produces abundance. Tjan, the business manager Kodacell brings in to help Perry and Lester, is well aware of this:

So, if you want to make a big profit, you’ve got to start over again, invent something new, and milk it for all you can before the first imitator shows up. The more this happens, the better and cheaper everything gets. It’s how we got here, you see. It’s what the system is for.

Price wars and Bertrand equilibrium

The mechanism that drives the “destruction” part of creative destruction in Makers is cut-throat price competition. Innovative products are undercut by imitators, who scoop up the entire market thanks to lower prices. The process is iterated until the price reaches cost (including an acceptable remuneration of risk and capital):

In a good market, you invent something and charge all the market will bear for it. Someone else figures out how to do it cheaper, or decides they can do it for a slimmer margin […] and so you have to drop your prices to compete. Then someone comes along who’s less greedy or more efficient than both of you and undercuts you again, and again and again, until eventually you get down to […] a baseline that you can’t get lower than, the cheapest you can produce and stay in business.

This is Tjan speaking on his first night at the Perry – Lester venture. To an economist, he is giving a texbook rendition of Bertrand competition, a price war leading to a zero-profit equilibrium.

Unemployment and labor economics issues

Creative destruction rearranges production factors in the economic system, supposedly for the good. Unfortunately, some of these elements are people, and rearranging may involve a lot of pain, humiliation and fear. Doctorow embeds labour economics issues deep into the novel: the Kodacell press conference is interrupted by a protest of laid off staffers. Kettlewell’s first email to Suzanne asks the big question looming underneath Makers:

What happens when all the things you are good at are no good to anyone anymore?

Research initiated at the beginning of the current recession has cast doubts about the possibility to successfully mass-retrain a laid-off workforce to adjust to the changing needs of an innovation economy (New York Times). Labour supply seems still oriented to selling man-hours and expecting to be managed in a more or less traditionally Tayloristic way.

Brian Arthur’s building-block innovation

When Suzanne reaches Perry and Lester’s den to be shown what it is they do, Perry demonstrates their method to technical innovation. Basically, it consists of recombining existing technology in new ways. This is not only possible, but dirt cheap and fundamentally easy, because, in Perry’s words

Everywhere you look there’s devices for free that have everything you need to make anything do anything.

And Lester is even more concrete:

You know how they say a sculptor starts with a block of marble and chips away everything that doesn’t look like a statue? Like he can see the statue in the block? I get like that with garbage: I see the pieces on the heaps and in roadside trash, and I can just see how it can go together.

Makers subscribes to the complexity theory’ view on innovation, as discussed by John Holland, Brian Arthur and other researchers: making new things is (mostly) about finding new ways to recombine existing building blocks. Successful combinations become, in their turn, new blocks, so that an initially simple technology (the famous six simple machines of the ancient greeks) bootstraps to increasing levels of sophistication.

Open source and the speed of creative destruction

Perry and Lester’s ability to combine technological building blocks is greatly enhanced by the fact that anything important to them can be performed by open source technologies. This enables them to develop working prototypes from off-the-shelf equipment and software and put them into a manufacturing pipeline without worrying about licensing issues. This has two consequences: first, in the world of Makers ecosystems develop preferably around open source technology, because people like Perry and Lester have every incentive to route around proprietary technology; second, that the speed of the creative destruction cycle is greatly increased.

I think this may be the most important intuition Makers has to offer. Just think: we increasingly buy in ecosystem (Mac-iPhone-iPad-MobileMe, or Google-Android-Google Apps, or Linux-Apache-IBM’s proprietary web solutions); ecosystems grow faster if they can build on open source building blocks, so that the open source ones tend to outcompete the proprietary ones in the long run; but innovations in open source ecosystems are almost impossible to protect, and that lowers their average margin as the highly profitable grace period gets shorter. The solution, as Tjan suggests (see above) and most policy makers worldwides agree, is to increase the pace of innovation. This, however, raises the question of just how fast consumers can wrap their head around innovation: every heavy web user is familiar with the sensation that companies are putting out new services faster than we can absorb them, and sometimes we just have no time for them, no matter how cool they are. Google Wave, anyone? So, it could be that the destruction side of creative destruction prevails, landing the economy of Makers into a state of low margins and low growth, as more inventions fail to turn into more successful products on the market.

Becattini and Brusco’s competitive-cooperative manufacturing systems

Perry and Lester run a very small business unit (themselves and a few helpers), so their global competitiveness depends on the neutrality of unit costs with respect to production volume – in other words, no economies of scale. In fact Perry and Lester’s Florida junkyard is a scale-efficient production unit. In Tjan’s words

Every industry that required a factory yesterday requires a garage today.

Of course, it’s hard to get away from the fact that a lot of the cheapness in the system comes from exploiting economies of scale. The trick is that component manufacturing is scale-intensive, but the artifacts that Perry and Lester are interested in, being assemblies of such components, have a much lower minimum efficient production scale. In such a scenario, manufacturing systems most fit to compete are those that combine the agility of horizontal and vertical disintegration with low transaction costs, mutual trust and informational transparence. Vertical disintegration lets firms grow large where there are economies of scale to be exploited (components, silicon chips); horizontal disintegration enhances competition in the finished goods market (even though whichever manufacturers will win out in any given period of time will still buy components from the same handful of suppliers, therefore saving on the costs of reallocation of workers and manufacturing capacity); low transaction costs enable vertically disintegrated “manufacturing“ units like Perry and Lester’s (mostly R&D and business development, really) to build ad hoc networks of suppliers fast. In other words, New Work displays both tough competition and cooperation over and above formalized contracts.

Sebastiano Brusco and Giacomo Becattini’s model of industrial districts display just these characteristics (as, with different nuances, the work of researchers as Charles Sabel, Michael Piore and Annalee Saxenian). In Makers the low transaction costs part is implemented top-down through networked company Kodacell rather than, as in Brusco and Becattini, bottom-up through evolving conventions and reputation effects in a small territory, home to all the forms involved. So, when Lester invents Home Aware, an ecosystem can be summoned out of Kodacell’s decentralized “teams” structure. Tjan explains:

There are ten teams that do closet organizing in the network, and a bunch of shippers, packers, movers and storage experts. A few furniture companies. […] The plan is to start our sales through the consultants at the same time as we start showing at trade shows for furniture companies.

The European Commission’s Living Lab

After a fire at a shantytown near the factory, Perry decides to let the inhabitants rebuild it on Kodacell premises (formerly a junkyard), which is largely unused. Kettlewell tries to get him to oust them. Perry holds his ground: he, Lester and Tjan had been meaning to invent something for the homeless people anyway.

We’ve built a living lab on our doorstep for exploring an enormous market opportunity to provide low-cost, sustainable technology for use by a substantial segment of the population who have no fixed address. There are millions of American squatters and billions of squatters worldwide. They have money to spend and no one else is trying to get it from them.

In the real word, Living Labs are a concept explored by the European Commission in the context of innovation policy. The idea is to replace consumer tests of new products with much larger scale, more realistic tests made possible a dense network of many actors collaborating on the same territory. Perry’s in-house shantytown would become a toy universe to model the squatters market: Kodacell can invent something and run a market test with limited costs and in a short time, but also real consumers spending real money. More importantly, it can recruit squatters themselves to participate in identifying needs and designing the products. And in fact it does: this is the role of the shantytown leader, Francis, who collaborates closely with Perry and Lester to think up new products.

Arrow’s Paradox and the value of invention

New Work’s downfall is heralded by an investor confidence crisis in Kodacell. Part of the problem is that analysts have a hard time figuring out how to value inventions, that are becoming an important part of Kodacell’s market value (the other part is inherent scarcity of genuine entrepreneurship). Kodacell ends up with a lot of novel products, with high returns on small projects. How many of these projects are going to scale to be large hits? Kettlewell:

Sure, if you looked at [our numbers] our way, they were great. If you looked at them the Street looks at them, we were in deep §#1t. Analysts couldn’t figure out how to value us.

This is yet another version of Kenneth Arrow’s famous paradox: markets for information typically don’t work well, because, in order to estimate precisely the value of something you need to know all about it. But information, of course, has no market value for you if you know it already. Invention is essentially information: until it is on the market and has climbed the diffusion curve, it is quite difficult to value it.

The New Work bust and the shift in consumer preferences

When part 2 of Makers opens, the New Work movement is over. A stock market bust has shattered the Kodacell business model, which had been promptly imitated by other large companies such as Westinghouse (who recruited Tjan off Kodacell). As a result, the movement is dead. Perry and Lester, still in their junkyard in Florida, start “the ride”, a sort of smart theme park-memorial of New Work, which is to be the subject of the rest of the book. The New Work fiasco is one of the least convincing parts of the book from an economist’s point of view: save for the aforementioned value of invention issue, it is hard to make out anything that would provoke more than a short-term market fluctuation. Kettlewell:

Analysts couldn’t figure out how to value us. Add a little market chaos and some old score-settling @##holes […] and it’s a wonder we lasted as long as we did.

Even less convincing is the ensuing consumer disaffection for the goods that New Work had produced. In Perry’s words:

No one cares about invention anymore.

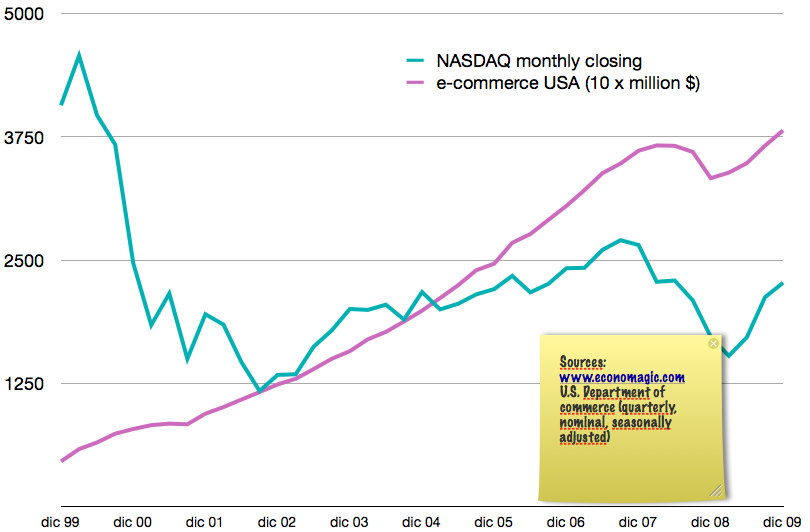

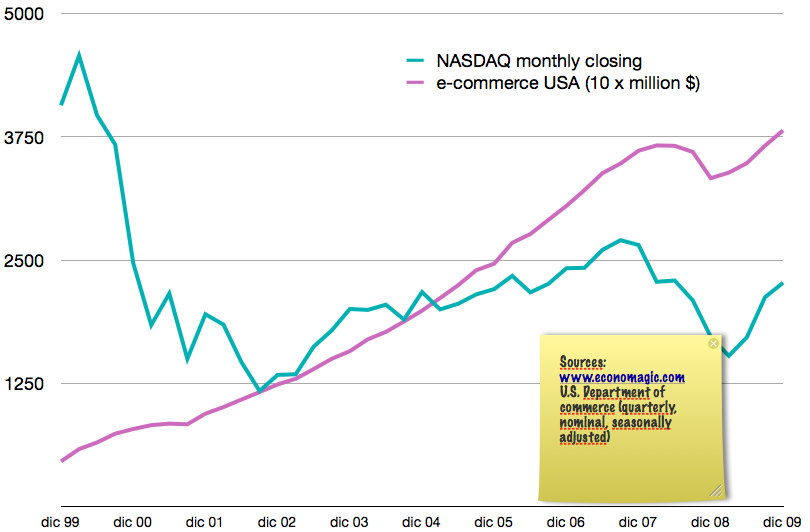

There is no obvious reason why this should happen. The second Perry-Lester invention, Home Aware, has been very successful, shipping a million units in six weeks. One would think that, even if the company originally producing it went bust, a competitor would step in to service and expand the existing customer base. After the 2000 dotcom bust consumers actually increased their use of the online services that they found useful, undaunted by their association with dotcoms. Yahoo, Google, Amazon and the like continued to prosper in their respective markets, if not in the stock market. I looked at time series data for NASDAQ and e-commerce sales over the period 1999-2009; the correlation between them is practically nonexistent (negative, in fact), as you can see from the following graph:

So, is the innovation society sustainable in Makers?

Sustainability questions are tricky. Time and again, scientists have made doomsday predictions that went viral as public opinion found them really convincing, but later turned out to be way off the mark. From Malthus to the Club of Rome and the Millennium Bug, we seem to have a bias towards underestimating the adaptability of our society and its economy (cultural change makes the birth rate drop, raising prices of oil increase the energy efficiency of GDP and so on). Doomsday feels right at some level: it may just be a heritage of our Neolithic past, or a very deeply ingrained cultural myth (Apocalypse, Ragnarok etc.). Certainly that suggests a lot of caution in predicting it.

The economics of New Work are at least plausible; its downfall is the least plausible of its features. I was expecting something like Kodacell and Westinghouse spinning off their New Work branches, or selling them to more nimble, lower overhead companies that would commodify the networked organization and finance that the giant companies have to offer. The history of open source has already shown that you don’t really need a large company to achieve coordination, after all. The book, however, ends on a deeply pessimistic note: the large evil company has won the battle against the ride movement and recruited Lester, neutralizing his innovative potential; Perry has become a sort of wandering troubleshooter, lonely and poor. Doctorow the economist seems to be supportive of the innovation society, but Doctorow the author definitely is not. I wonder – really wonder – which if the two Doctorows will be right in the end.