Three months into Edgeryders I am in awe at the generosity and the creativity with which so many young people take their journey through life. Some leave the career path that seems easiest, even at considerable personal sacrifices, insearch of something deeper; most desire to “do something useful”. They think big, and are not afraid to confront global problems like food security, the redesign of social ties, access to housing. All this energy is channeled into innovation, often marked by a refreshing radicality: urban farming, co-housing, social currencies, open public sector data, urban games to reappropriate public spaces, home schooling, peer-to-peer learning, you name it.

Three months into Edgeryders I am in awe at the generosity and the creativity with which so many young people take their journey through life. Some leave the career path that seems easiest, even at considerable personal sacrifices, insearch of something deeper; most desire to “do something useful”. They think big, and are not afraid to confront global problems like food security, the redesign of social ties, access to housing. All this energy is channeled into innovation, often marked by a refreshing radicality: urban farming, co-housing, social currencies, open public sector data, urban games to reappropriate public spaces, home schooling, peer-to-peer learning, you name it.

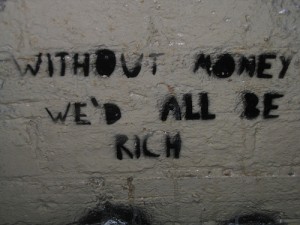

Innovators are a minority, as they always have been. But this minority differs from those of the past in two ways: it is numerically large, probably up in the millions, rather than the tens of thousands of a century ago; and it is self-selected, and internally very diverse. Though many innovators are members of the élites, with immaculate academic credentials, others are free spirits, university dropouts intolerant of departmental hierarchies, self-taught. The best indicator of the distance between young innovators and the élites is simple: so many of them are poor, barely able to make a living but not of amassing any wealth (hat tip: Vinay Gupta). There is a joke going around: if you are looking for the capital to launch a social innovation initiative, don’t waste your time asking banks, venture capitalists or governments agencies. The only people who support this stuff are “the three Fs”: family, friends and fools (hat tip: Alberto Masetti-Zannini).

The scale and diversity of the minority of innovators opens up the way to a completely new perspective: an adaptive innovation policy. Current public policies for innovation operate by selecting a priori, with the help of famous academics, a limited number of strategic research strands, normally framed in big science terms (like cold fusion or nanotech) and throwing money at them. A different approach has just become possible: do a great many small investments in a logic of diversification, letting a great many innovators choose which issues to tackle and how; monitor for lucky breaks or interesting solutions; and then scale the investiment on those that have already yielded something tangible. The idea is to reward innovative activities not for their direction, but for their results. This approach has the advantages of depending far less on the a priori wisdom of policy makers; and of discovering a posteriori which issues the innovators community finds more worthy of their efforts, and which lines of work are more likely to yield concrete results. It is a low-cost approach to evaluation, which can be very costly if you do it properly.

I was thinking about these things on Sunday, as I participated in a conference on basic income. Basic income is income decoupled from work or wealth: everybody has a right to it, just for existing. I am no expert, but I understood it is framed as a measure targeted at establishing the dignity of the individuals, making them more safe and harder to intimidate. All of this makes a lot of sense; still, I can’t help thinking that basic income could also be seen as an instrument of innovation policy: free from immediate need, (mostly young) citizens would be enabled to take some extra risks and try out more new ideas. Most would fail, as is always the case, but failures would be effectively too cheap to even meter, while successes could have large impacts, easily able to pay off the whole operation. I suspect the social cost of basic income would be near zero: people are surviving anyway, so the whole thing amounts to a reallocation of purchasing power from the wealthy and employed to the poor and unemployed.

All of this translates into an innovation policy mix that invests less on activities (lab research) and organization (corporate R&D units or universities) and more on people. The basic idea is give them the means to attack problems they care about solving, then get out of their way and, later, evaluate their results. It’s common sense, really, unless you think people – young people, in this case – are generally cynical, lazy or worse.