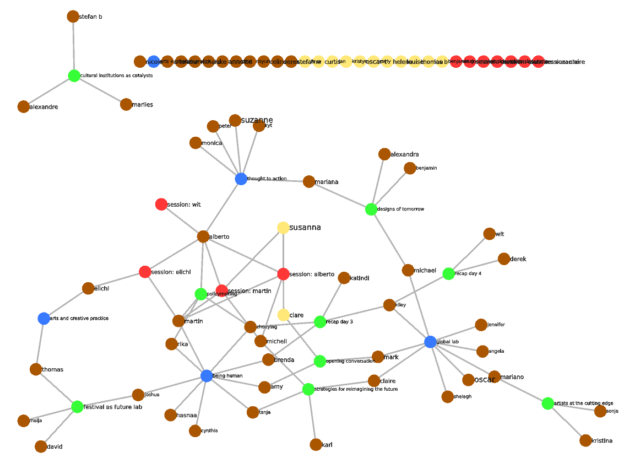

Folks at the Salzburg Global Seminar were kind enough to show interest in (or at least tolerate) my obsession for social networks and semantic social networks. So, I made a social network of our session, called “session 593” (a nice prime number, as Martin Bohle pointed out).

It works like this. There are five types of nodes: fellows (brown), staff (yellow), plenary panels (green), focus groups (blue) and impromptu breakout sessions (red). Staff and fellows “vote” participating in focus groups and breakout sessions. Additionally, SGS assigned many of us to plenary panels with others. Edges in the network are interpreted as “fellow X participated to event Y”.

The data are wildly incomplete. I compiled the lists of fellows, staff, and plenary panels from the program; the list of focus groups I made on the fly on the last day. The program also has data about who participated in which panel, so that’s there. Kiley’s latest two recaps count as panels, because she involved others in them (Katindi, Brenda, Zhouying…). As for the focus group compositions, I obviously knew the one I participated in, thought to action; I also was able to add two more (being human and global lab), based on the tables on the final session. I had started to map the arts and creative practice , but then the facilitator asked us to stand up and move the table, and there went my data integrity 🙂 I also do not know who participated into which session, except for a few (Martin’s, Eichi’s, my own…).

If the data were complete, you could start looking through which sessions connected who, which people spent lots of time together (this is done through a technique called projection), and even, with some reflection, who should have spent time together but did not – the missing edges in the network. With the incomplete data, it turns out that the global lab focus group had the highest eigenvector centrality (a measure of centrality that reflects the centrality of connecting nodes, like Google’s PageRank algorithm). It is also the session with the most participants.

If you were at SGS session 593, and are curious as to what this might look like, I am happy to try to complete it. I also vow to beautify it a bit – makes for a cool pic to put on your blog. I will need:

- From everyone, which focus group they participated to.

- From people who held breakout sessions, who came to their session.

I will update it as I receive data from you. I predict that the complete data would see a high centrality of Claire (Nelson) and her Moonshot session. 🙂

This network has no semantics, it’s just a social network. But still, networks speak to many people, myself included, and anyway doing something like this is easy.

If you are in the network, and prefer not to be included in the network, let me know and I will remove you at once.