A little more than four years ago David Osimo convened a workshop in Brussels with the title Public Services 2.0. It was quite new for the context, both in method (the European Commission was asked only to provide e room and wi-fi connection, while speakers and participants donated their time and even paid their own travel expenses) and in content (a peer dialogue among person that were already delivering – as opposed to proposing public policies through the Internet. Many Commission officers showed up, probably moved by curiosity: who were these people who dared to mix two ingredients coming from two totally different spheres? Why did they seem not to ask anything of the Commission itself, and seemed more motivated by talking to each other?

That workshop turned out to be foundational. With some of the people and the projects (like MySociety or Social Innovation Camp) that I met there for the first time I started a dialogue that continues to this day, and from which I learned much. At the time I was the director of Kublai, a much-praised but little imitated (or at least little wellimitated) project: in Brussels I found out that my team and I were part of a global movement, still tiny but determined to change forever the way to think about public policy.

Our small “homemade” movement has grown a lot, though it remained a minority. And today it prepares yet another step: Policy Making 2.0, a conference that wraps up two years of preparation of a road map (commentable here for research on public policies in the Internet age: what are the trends? What the promising leads, the main roadblocks? What is missing? No way I am going to miss it. This is an interesting and urgent discussion if the open government community is to work side by side with the scientific community.

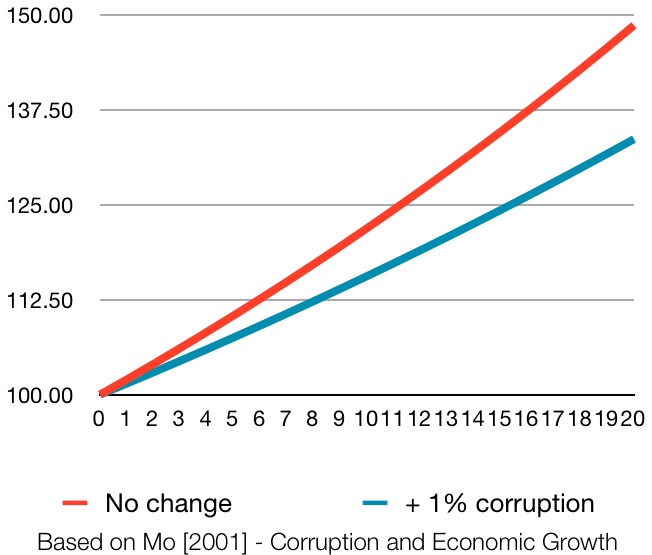

For good measure, David has added a prize for policy making 2.0, and even asked me to be one of the judges. Any project out there that wants to claim it? I would be delighted to support some intelligent, brave civil servant. A few weeks ago, the open data community received a bit of a shock, in the form of a sharp, well-argued critique by Evgeny Mozorov. He claims that the “open government” meme hides a disconnect between those of us who interpret openness as transparency, accountability and ultimately human rights; and those that interpret it as contendibility to market competition, efficiency and GDP generation. In the extreme, he argues, “open government” can be made to mean “government open to competition from the private sector for the management of public goods”. I agree with Mozorov that the difference in approach is there. However, I propose a point of view to reconcile the two different outlooks in practice. To do this, I borrow the words of the Italian blogger Michele Vianello, whom Mozorov would place firmly in the “openness for growth” camp. Michele is unconvinced by the sort of data that the Italian open data movement advocates the opening of. How can we not understand that the most important data to open are those that enable citizens, businesses and government to generate economic and social value? […] How many GDP percentage points do we gain by live streaming the meetings of the parliamentary commissions? Michele’s idea seems similar to what Mozorov attributes to the O’Reilly camp: 1 is the point debated by Mozorov. It comes down to what your values are. Let me leave it at that for now – I’ll come to it in a moment. 2 is definitely false – in the scientific sense of being contradicted by a veritable tide of economic literature. In the case of Italy, Corte dei Conti, our top administrative tribunal, estimates that corruption costs 60 billion euro a year. A few years ago this paper was quite popular (and there are many others). It says: increasing corruption by 1% (measured by polling indicators: corruption is by definition elusive to measure “at the tap”) implies a decrease of the GDP’s growth rate by a bit more than half a percentage point. Over the years, obviously, foregone growth itself follows an exponential growth curve – compound interest is an ugly beast – so that even small differences in the levels of corruption can lead to large ones in the absolute levels of national wealth. In the following chart I imagine two initially identical economies (GDP at time 0 = 100), which would each grow by 2% a year in the absence of changes in their levels of corruption. I then posit that one of the two experiences a 1% increase in the levels of corruption in year 1. Following Mo, 2001 quoted above, this decreases its rate of growth by 0.54 percentage points. Corruption levels and everything else remain stable thereafter. Twenty years later, the GDP of the more virtuous economy has a fifteen percentage points lead on the less virtuous one. Not by chance, the World Bank, OECD, UNDP and every other development agency worth its salt is turning an increasingly interested eye to pro-transparency, anti-corruption policies. Nor is it just corruption: the combination of open data, a lively data journalism scene and an attentive public opinion can help improve the effectiveness of public spending executed legally but poorly, that follows the same mathematical logic in decreasing growth. This is the rationale behind projects like Opencoesione (public expenditure data on over 600,000 projects funded with regional cohesion funds). Remember Linus’s Law: given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow. Now, open data are not only a component of transparency; my experience (and, I think I can say, the Italian community’s – just look at Spaghetti Open Data) is that they generate additional demand for transparency, drive to better understand, order in the data generation and in the policy process. Conclusion: we, the open government/open data community, can disagree about our value system. But in practical terms, value systems does not make a lot of difference: we should all support radical transparency policies. If you agree with Mozorov, you will do it because you think we all have a right to know in depth what the government (and, hopefully in the near future, corporates) is doing, since that impacts our lives. If you agree with Vianello, you’ll do it because it’s good for GDP. Either way, the economic impact of open data has a tried and true channel for economic impact via increased efficiency in the overall economy from transparency; it’s there and it is solid. At the time of writing, it looks far more solid than impact via jobs created by startups that sell apps on Apple’s AppStore or Google’s Play. Here’s the background: by the end of 2011 the government was convinced that the battle for the rule of law and a decent life for all in Italy’s Mezzogiorno would be won or lost in Pompeii, a symbol of the battle itself. In a very short time, three ministers – culture, interior and regional cohesion) set up a hundred-million euro project to restore the insulae damaged by the rain (a scourge of all open-air archaeological sites); got the European Commission’s seal of approval; wrapped it into an advanced security model that should keep mob-polluted companies to win any tenders. Thus was born the Great Pompeii Project. As a very minor integration of this massive project, the government decided in 2012 to launch a small initiative for transparency, inquiry and mobilization. Spending on culture is great; protecting that spending against criminal infiltration is even better; but neither is enough. Public spending must be not just legitimate, but effective and efficient. It was decided that releasing the spending data from the Great Pompeii project must be a step in the right direction. Access to data and data-powered public debate can help to discover errors suggest improvements, drive administrations to perform better. On this intuition, OpenPompei was born. Its remit has been kept broad on purpose, and includes: The dream behind OpenPompei is to help build an alliance of civic hackers, non-compromised enterprises and State to maintain a high level of attention on public spending, so as to fight corruption and increase efficiency. It is unlikely for a small, peripheral project to achieve such a lofty goal, but we hope to give a contribution – at least one of knowledge. To guarantee its independence, OpenPompai was set up as a European-funded project. Studiare Sviluppo, a in-house company of the ministry of the economy, was tasked with delivering. I worked with them before on Visioni Urbane e di Kublai. Wish me well, and be there for me when the going gets rough, ok?

A questo giro, David si è inventato anche

This entry was posted in Open government and tagged CrossoverEU, David Osimo, MySociety, Policy Making 2.0, research, Social Innovation Camp on .

Trasparency brings growth

OpenPompei: open data and the hacker economy vs. the mob

I’ve got a new task. I will run a new project called OpenPompei. It is part of the government’s new strategy in the Naples area, and in particular Pompeii.