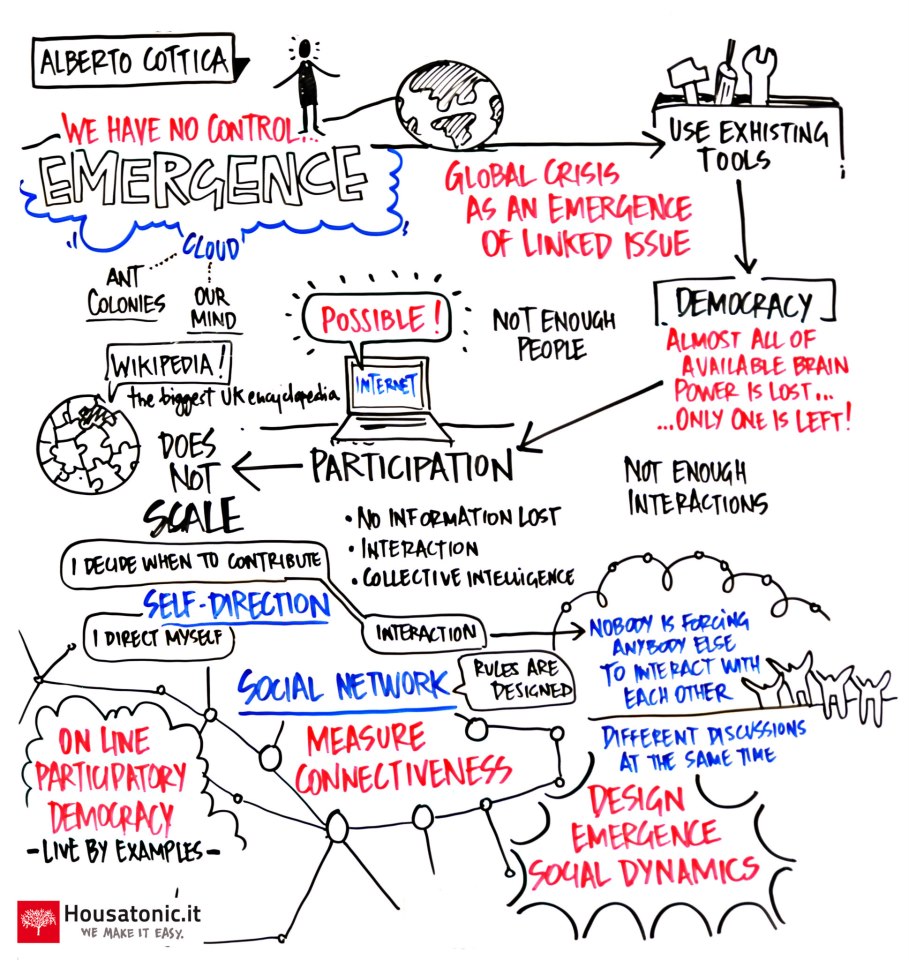

So, I care about democracy, and dream about fixing it. For years, and in many different contexts, I have been weaving narratives of collaboration between citizens and their institutions towards the common good. These narratives have provided ideological scaffolding for creatives, radical changemakers and civil servants to work together, reaping the benefits of diversity and discovering that they can get stuff done.

This, however, is getting harder and harder. Global problems press humanity on (take your pick: climate change, feral finance, loss of biodiversity, mounting inequalities); a globally connected citizenry, fueled by the Steve Jobs-Obama ideology of change as desirable, possible, a moral imperative even, has raised their expectations levels. Institutions, while probably not moving any slower than they did twenty years ago, have failed to keep up with the acceleration. The result is a sort of (negative) credibility singularity: you can feel people getting more impatient by the week. And not without reason: the failure to take serious action on climate change after decades of talk is very hard to justify outside the institutions’ corporate walls. What could any government agency answer to Anjali Appadurai’s passionate call to action in the video above? “Give us ten years!” to which her answer is “You just wasted twenty”. “We must not be too radical”, to which her answer is “Long term thinking is not radical”. What is there to say? She’s right.

The singularity point itself is the place where people decide democratic institutions are not delivering, and route around them to get things done. I am not looking forward to it. In fact, I happen to think democratic government institutions are still humanity’s best asset towards cooking up a coordinated, global response to global threats. But if this is to happen, a lot more radical thinking needs to take roots in Brussels (and Rome, and London, and Washington D.C. etc.). And to do it fast, while credibility can still be restored.

(Thanks: Vinay Gupta and Jay Springett)