I just saw a very inspiring exhibition called Das Rote Wien, (“Red Vienna”) at the Wien Museum. I want to make a quick note of what I saw, since it relates to our reflection around The Reef.

Background: Vienna is, even today, unique. A large percentage (about 20%) of all apartments for rent in the city are owned by the municipality (Gemeinde Wien). Additionally, they are not concentrated in one or few low income areas, but are scattered all across the city. There are no ghettos in Vienna.

The foundations for this state of affairs were laid in a short period, from 1919 to 1933, called “Red Vienna”. Here is how I understand the situation:

- The Austrian Empire loses World War 1 and much of its territory. It morphs into a federal republic and turns to socialism. Socialist ideas spread: about the dignity of man, the centrality of urban workers in society, and the role of the state in bringing about a new kind of society. The Socialist party wins a majority in the federal parliament.

- In 1919, it loses control of the federal government, but maintains a high consensus in Vienna (about 50% of votes throughout the period preceding Austria’s assimilation into Nazi Germany). Socialists refocus on Vienna as the cradle of their utopia.

- Meanwhile, post-war hyperinflation has swept away public debt.

- Rent controls are established in 1917. This ends real estate speculation and leads to falling real estate prices.

- In 1922 Vienna is separated from the rest of Lower Austria, and becomes its own state (Land). It can now levy its own taxes. This enables a radical, and very successful, fiscal policy:

These taxes were imposed on luxury: on riding-horses, large private cars, servants in private households, and hotel rooms. (To demonstrate the practical effect of these new taxes, the municipality published a list of social institutions that could be financed by the servants tax the Vienna branch of the Rothschild family had to pay.)

Another new tax, the Wohnbausteuer (Housing Construction Tax), was also structured as a progressive tax, i.e. levied in rising percentages. The income from this tax was used to finance the municipality’s extensive housing programme. Therefore, many Gemeindebauten today still bear the inscription: “Erbaut aus den Mitteln der Wohnbausteuer” (built from the proceeds of the Housing Construction Tax). (Wikipedia)

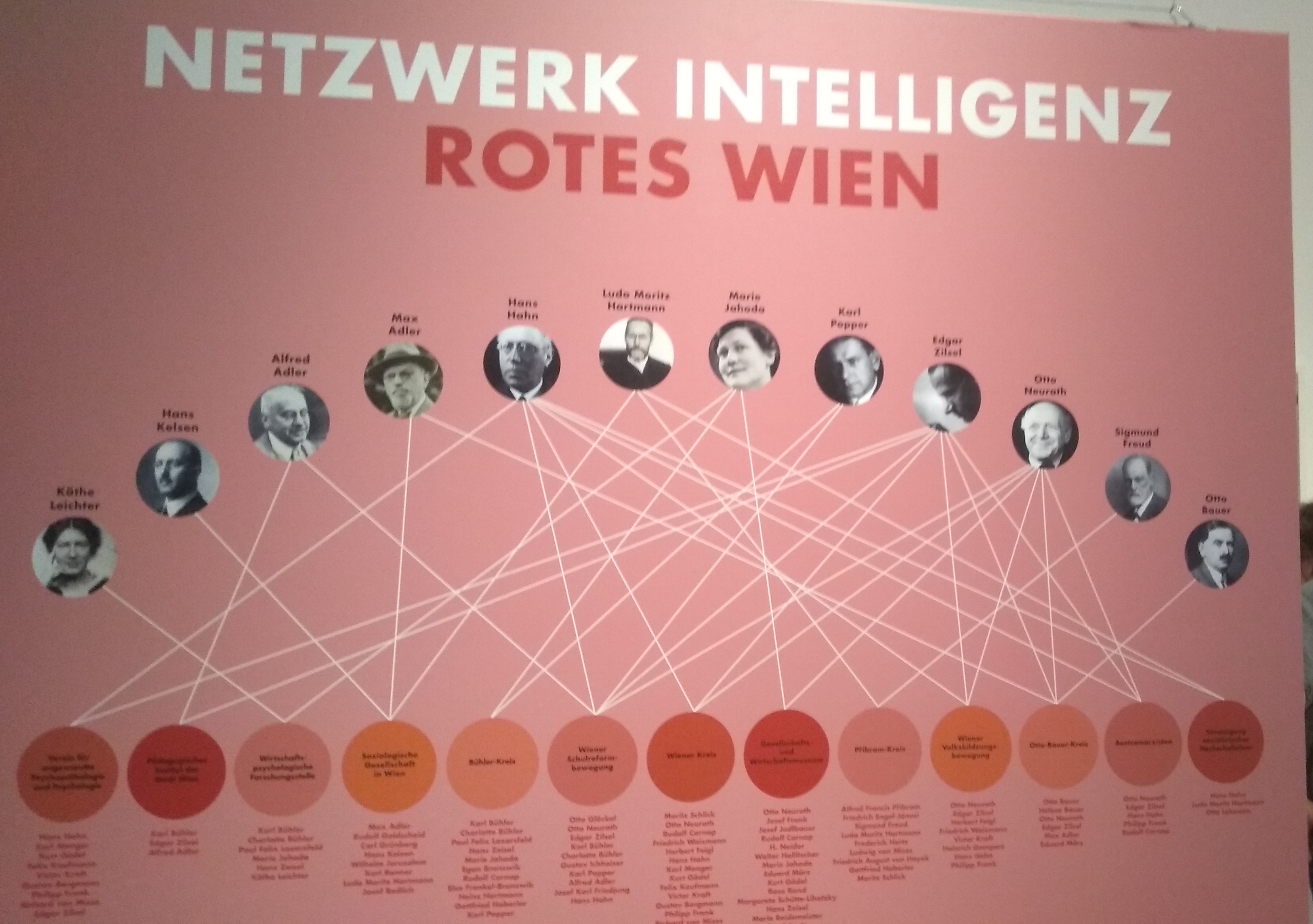

- Red Vienna deploys substantial intellectual firepower. Socialists mobilize Freud, Adler, Popper, Gödel, Loos, Neurath and others, and offer them seats on boards of research- and policy institutions. The exhibition has an impressive visualization of the Netzwerk Intelligenz, showing how these intellectuals worked with one another in various organizations contributing to the city’s governance.

- Red Vienna works across the policy spectrum to implement the socialist vision: education reform, social services, health care, green areas. Housing is a central concern. In fact, Viennese citizens had not been waiting around for socialist leaders to make up their minds, and had taken that matter into their own hands.

Following the war, thousands of “wild” settlers occupy land on the periphery of Vienna, where they erect simple dwellings and grow gardens for their food. Emerging from this is the cooperative-oriented Viennese settler movement. Architects and intellectuals, such as Adolf Loos, Margarete Lihotzky, and Otto Neurath see a new democratic way of living in the simplicity and functionality of settlement houses.

- In a very creative move, the city government decides to support, rather than repress, this movement:

- In order to guide the settlement activity and certainly also to control it politically, the municipality provides the settlers financial and technical support beginning in 1920. By 1933, roughly 8,000 settlement houses had been built in Vienna.

- In 1923 Red Vienna moves beyond surfing the wave of the settlements movement, and rolls out a full-fledged strategy. It consists of the already mentioned Wohnbausteuer, earmarked to finance the city’s affordable, high-quality housing strategy, and of a construction plan. The latter is another innovation:

“New Vienna” is not developed as residential estates in the periphery, as is the favored practice internationally, but unstead, is integrated into the existing city in the form of several-story “people’s apartment buildings”. […] All of the rooms are furnished with windows, and all of the apartment have running water and toilets. Their rather moderate dimensions are extended by communal spaces, such as laundry rooms and baths. Until 1933 approximately 380 council housing buildings are constructed, with more than 60,000 apartments able to house 200,000 people.

So, in less than 15 years, Vienna built 60,000 apartments, plus 80,000 settlement houses. Assuming an average of 4 inhabitants per house, this means lodging 200,000 people with the New Vienna program + 320,000 people with the bottom-up settlements. This runs up to 520,000 people… in a city of 1,700,000 inhabitants!

These buildings brought about a huge increase in the quality of urban life, and in that of Vienna’s landscape. This increase was permanent: almost all lodgings are still in use today, 100 years after Red Vienna, and Vienna is always topping the charts of the most livable cities in the world. This, despite the Nazis ending Red Vienna in civil war and ultimately annexation in 1933.

It appears we have

There are so many valuable lessons in here that I do not even know where to start. Maybe it is even more interesting to consider the interplay of the various factors: preconditions like Vienna’s debtlessness and the “plasticity” of the Austrian constitutional architecture, and therefore the city’s power to levy taxes (courtesy of losing a major war); intellectual resources (mostly inherited by imperial times); bold policy; and an impressive ability to “sniff the wind” and channel and support emergent phenomena like the informal settlements, rather than fight them back.

It would be worth looking deeper into the matter. Unfortunately many sources are available only in German. Does anyone have any insights to offer?

(Reposted from Edgeryders)