Category Archives: default (en)

Redesigning urban living at scale: the case of “Red Vienna” in the 1920s

I just saw a very inspiring exhibition called Das Rote Wien, (“Red Vienna”) at the Wien Museum. I want to make a quick note of what I saw, since it relates to our reflection around The Reef.

Background: Vienna is, even today, unique. A large percentage (about 20%) of all apartments for rent in the city are owned by the municipality (Gemeinde Wien). Additionally, they are not concentrated in one or few low income areas, but are scattered all across the city. There are no ghettos in Vienna.

The foundations for this state of affairs were laid in a short period, from 1919 to 1933, called “Red Vienna”. Here is how I understand the situation:

- The Austrian Empire loses World War 1 and much of its territory. It morphs into a federal republic and turns to socialism. Socialist ideas spread: about the dignity of man, the centrality of urban workers in society, and the role of the state in bringing about a new kind of society. The Socialist party wins a majority in the federal parliament.

- In 1919, it loses control of the federal government, but maintains a high consensus in Vienna (about 50% of votes throughout the period preceding Austria’s assimilation into Nazi Germany). Socialists refocus on Vienna as the cradle of their utopia.

- Meanwhile, post-war hyperinflation has swept away public debt.

- Rent controls are established in 1917. This ends real estate speculation and leads to falling real estate prices.

- In 1922 Vienna is separated from the rest of Lower Austria, and becomes its own state (Land). It can now levy its own taxes. This enables a radical, and very successful, fiscal policy:

These taxes were imposed on luxury: on riding-horses, large private cars, servants in private households, and hotel rooms. (To demonstrate the practical effect of these new taxes, the municipality published a list of social institutions that could be financed by the servants tax the Vienna branch of the Rothschild family had to pay.)

Another new tax, the Wohnbausteuer (Housing Construction Tax), was also structured as a progressive tax, i.e. levied in rising percentages. The income from this tax was used to finance the municipality’s extensive housing programme. Therefore, many Gemeindebauten today still bear the inscription: “Erbaut aus den Mitteln der Wohnbausteuer” (built from the proceeds of the Housing Construction Tax). (Wikipedia)

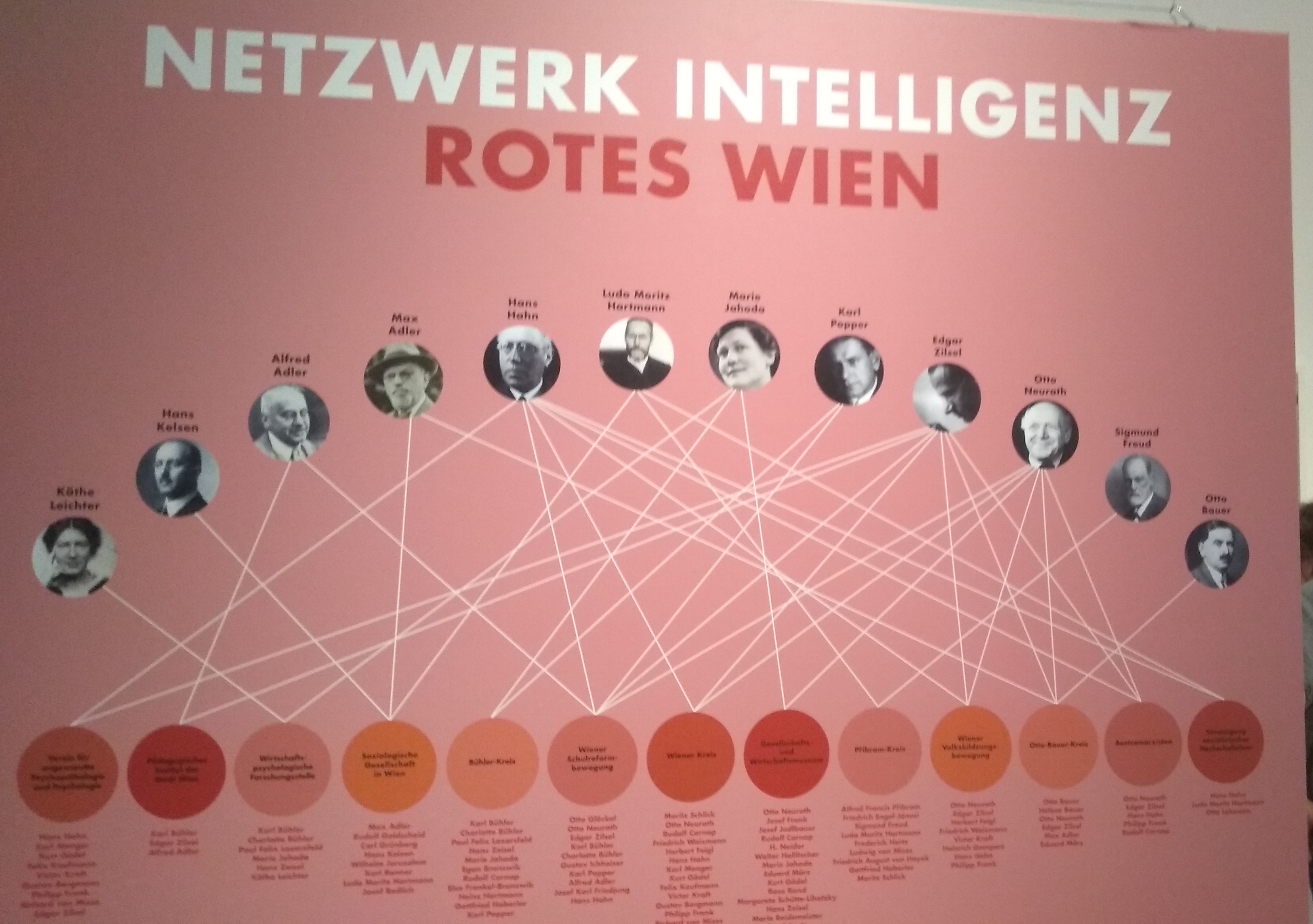

- Red Vienna deploys substantial intellectual firepower. Socialists mobilize Freud, Adler, Popper, Gödel, Loos, Neurath and others, and offer them seats on boards of research- and policy institutions. The exhibition has an impressive visualization of the Netzwerk Intelligenz, showing how these intellectuals worked with one another in various organizations contributing to the city’s governance.

- Red Vienna works across the policy spectrum to implement the socialist vision: education reform, social services, health care, green areas. Housing is a central concern. In fact, Viennese citizens had not been waiting around for socialist leaders to make up their minds, and had taken that matter into their own hands.

Following the war, thousands of “wild” settlers occupy land on the periphery of Vienna, where they erect simple dwellings and grow gardens for their food. Emerging from this is the cooperative-oriented Viennese settler movement. Architects and intellectuals, such as Adolf Loos, Margarete Lihotzky, and Otto Neurath see a new democratic way of living in the simplicity and functionality of settlement houses.

- In a very creative move, the city government decides to support, rather than repress, this movement:

- In order to guide the settlement activity and certainly also to control it politically, the municipality provides the settlers financial and technical support beginning in 1920. By 1933, roughly 8,000 settlement houses had been built in Vienna.

- In 1923 Red Vienna moves beyond surfing the wave of the settlements movement, and rolls out a full-fledged strategy. It consists of the already mentioned Wohnbausteuer, earmarked to finance the city’s affordable, high-quality housing strategy, and of a construction plan. The latter is another innovation:

“New Vienna” is not developed as residential estates in the periphery, as is the favored practice internationally, but unstead, is integrated into the existing city in the form of several-story “people’s apartment buildings”. […] All of the rooms are furnished with windows, and all of the apartment have running water and toilets. Their rather moderate dimensions are extended by communal spaces, such as laundry rooms and baths. Until 1933 approximately 380 council housing buildings are constructed, with more than 60,000 apartments able to house 200,000 people.

So, in less than 15 years, Vienna built 60,000 apartments, plus 80,000 settlement houses. Assuming an average of 4 inhabitants per house, this means lodging 200,000 people with the New Vienna program + 320,000 people with the bottom-up settlements. This runs up to 520,000 people… in a city of 1,700,000 inhabitants!

These buildings brought about a huge increase in the quality of urban life, and in that of Vienna’s landscape. This increase was permanent: almost all lodgings are still in use today, 100 years after Red Vienna, and Vienna is always topping the charts of the most livable cities in the world. This, despite the Nazis ending Red Vienna in civil war and ultimately annexation in 1933.

It appears we have

There are so many valuable lessons in here that I do not even know where to start. Maybe it is even more interesting to consider the interplay of the various factors: preconditions like Vienna’s debtlessness and the “plasticity” of the Austrian constitutional architecture, and therefore the city’s power to levy taxes (courtesy of losing a major war); intellectual resources (mostly inherited by imperial times); bold policy; and an impressive ability to “sniff the wind” and channel and support emergent phenomena like the informal settlements, rather than fight them back.

It would be worth looking deeper into the matter. Unfortunately many sources are available only in German. Does anyone have any insights to offer?

(Reposted from Edgeryders)

The practices of online community management: the results are in

Online communities are all around us. I myself spend a lot of time on Edgeryders and Spaghetti Open Data, and there are countless others. Most of these communities are managed in one form or other – in fact, both online communities and their management predate the Internet itself. But what do online community manager actually do? How do they spend their time? There is quite a lot of lore and anecdotes out there, but it is hard to have an idea of how representative they are.

As part of a larger work (my Ph.D. thesis), I decided to try to answer this in a more systematic way. Here is what I did.

Methodology and questionnaire

I started by scanning the academic and business literature on online community management looking for practical advice. From it, I extracted a list of practices. The list is this:

- Invite users to join [Young 2013, Iriberri 2009, Kraut 2011].

- Welcome new users when they sign up [Kraut 2011, Kim 2000, Ganley 2009, own experience].

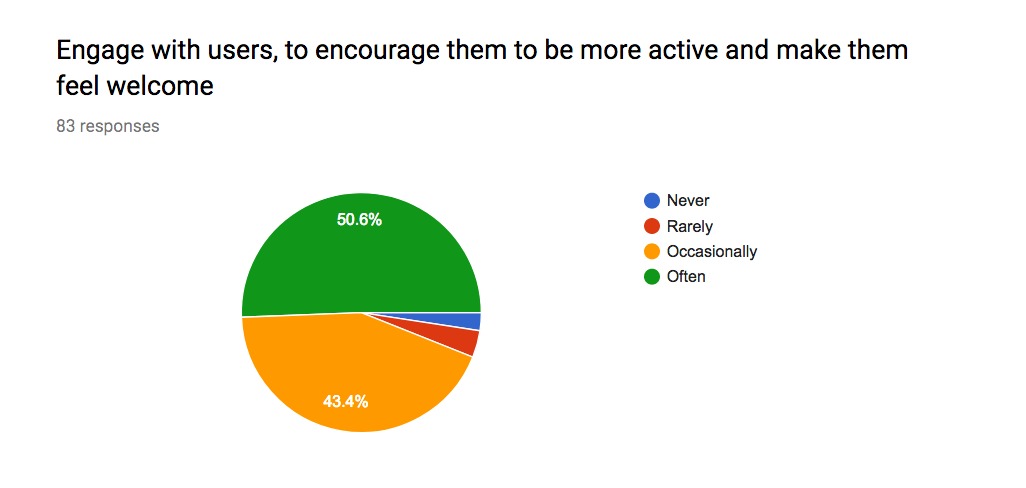

- Engage with users, to encourage them to be more active and make them feel welcome [Young 2013, Ludford 2004, Williams 2000, Kim 2000, Kraut 2011, own experience].

- Mediate conflict (Kim 2000, Kraut 2011].

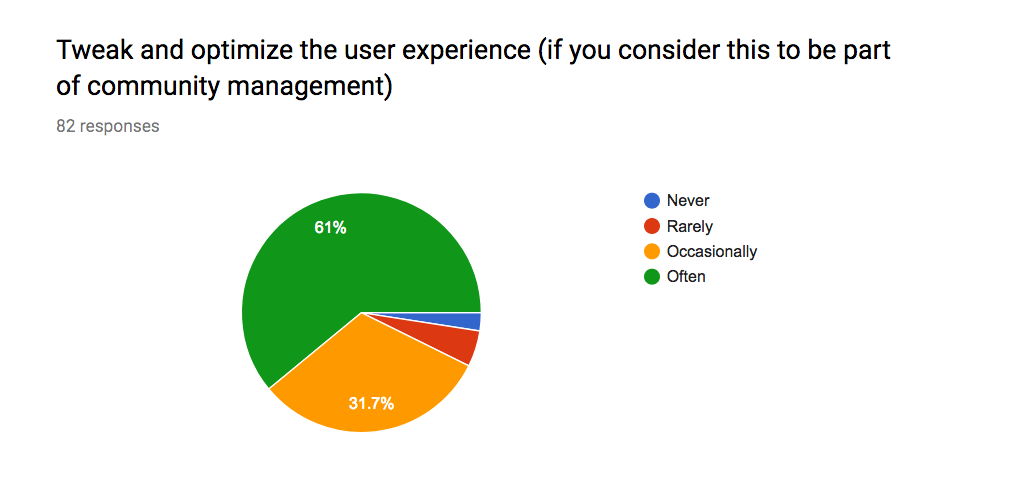

- Tweak and optimize the user experience (if you consider this to be part of community management) [Kraut 2011, Kim 2000].

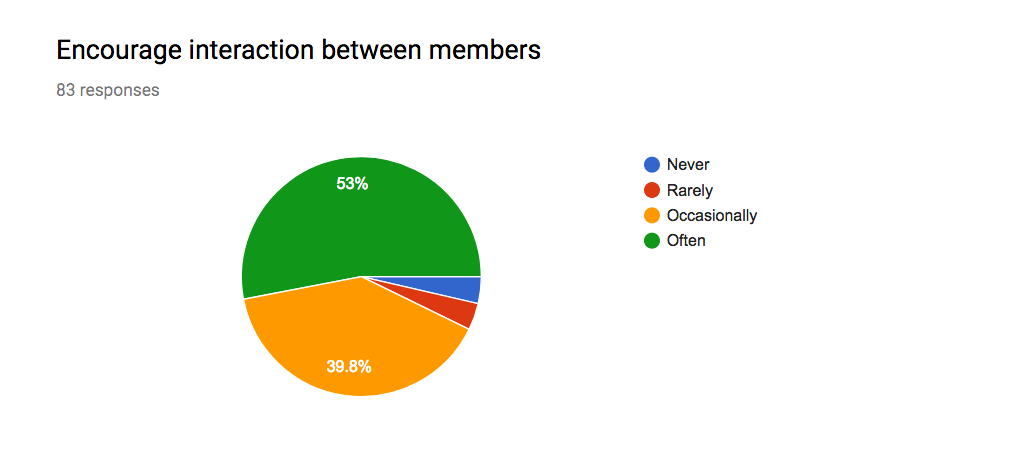

- Encourage interaction between members (Ganley 2009, Williams 2000, Kraut 2011, own experience).

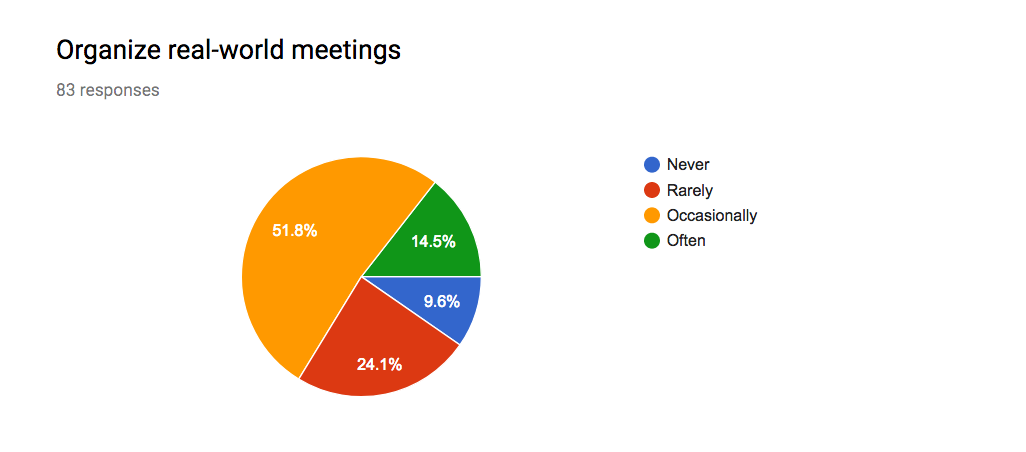

- Organize real-world meetings (Kim 2000, own experience).

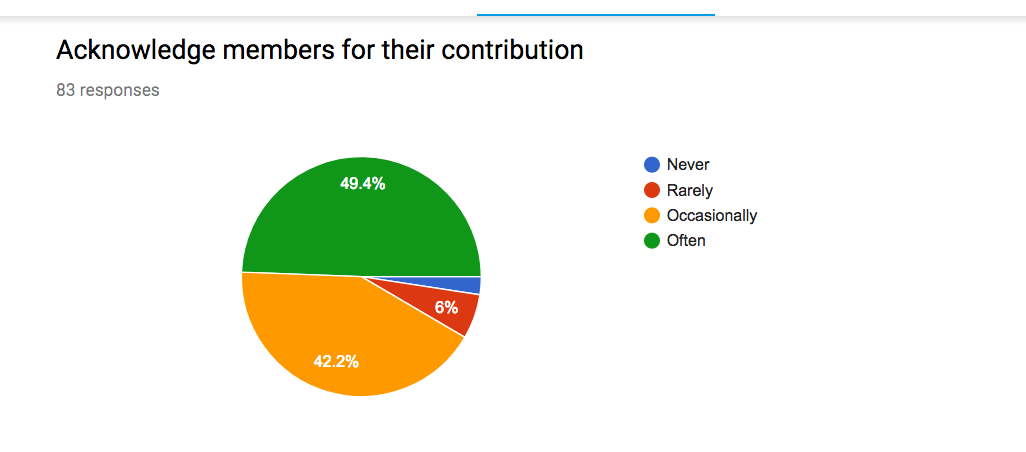

- Acknowledge members for their contribution (Kraut 2011, Ludford 2004).

- Support volunteers (Kim 2000, Young 2013, Williams 2000, Kraut 2011).

Then, I prepared a questionnaire that had one question for each practice of the list. The academic references (given in full at the end of this post) were not included in the questionnaire, to avoid influencing respondents. For each practice in the list, respondents were asked to answer (by multiple choice) the following question:

To manage your online community, which of these courses of actions do you take, and how often?

Next, I included a question to allow respondents to point to practices not in the list. Answers were given in free-form text.

Do you want to add any other activity that uses up significant chunks of your community management time?

Finally, I added two more questions for context. Answers were given by multiple choice.

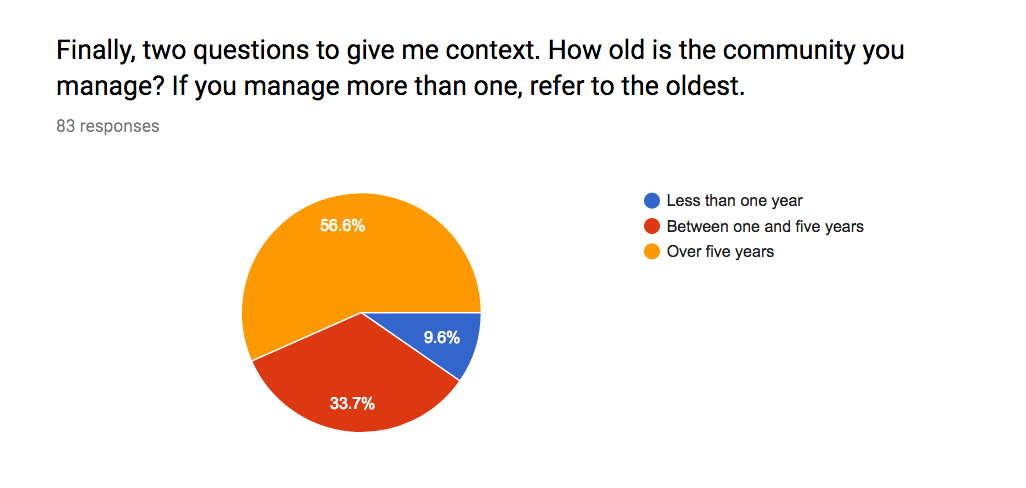

How old is the community you manage? If you manage more than one, refer to the oldest.

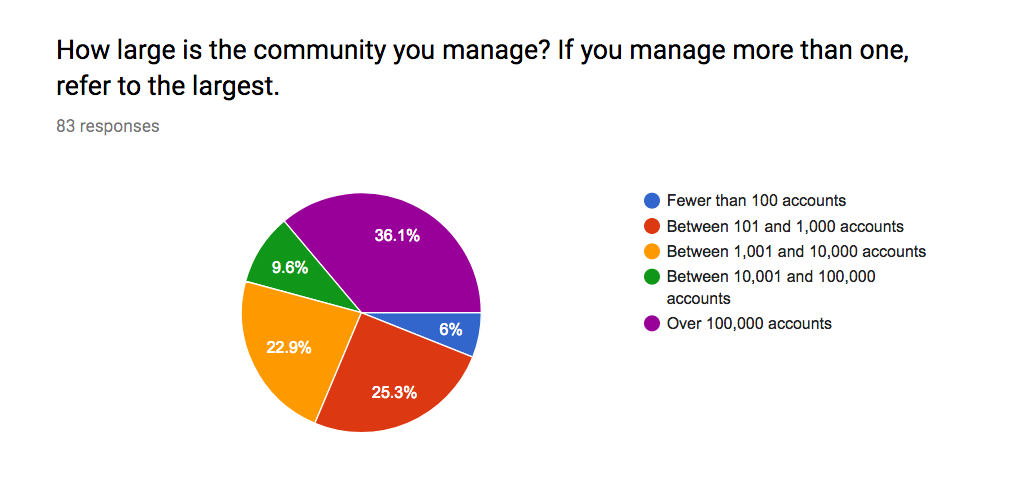

How large is the community you manage? If you manage more than one, refer to the largest.

I created a post on this blog that contained some context information and linked to the questionnaire itself on Google Forms. Post and questionnaire went live on March 13th 2018. I created a shortlink via bit.ly pointing to the information page, and disseminated via my own Twitter and Facebook accounts. I also posted it on e-mint, a long-running Yahoo! group populated by professional online community managers, and on CMX Hub, a community of community managers on Facebook.

I have collected results on March 31st 2018. At that date, my shortlink had collected 210 clicks. bit.ly reports that 101 came from Facebook; 78 from e-mail or direct; 25 from Twitter. Geographically, most visitors came from the United States (82), Italy (49), the UK (23). These visits resulted in 83 completed questionnaires. This is an amazing result! I am very grateful to everyone who responded and spread the interest for my little initiative. In particular, I suspect that the benevolence of my friend John Coate and the e-minters played a large part in this success.

Results and data

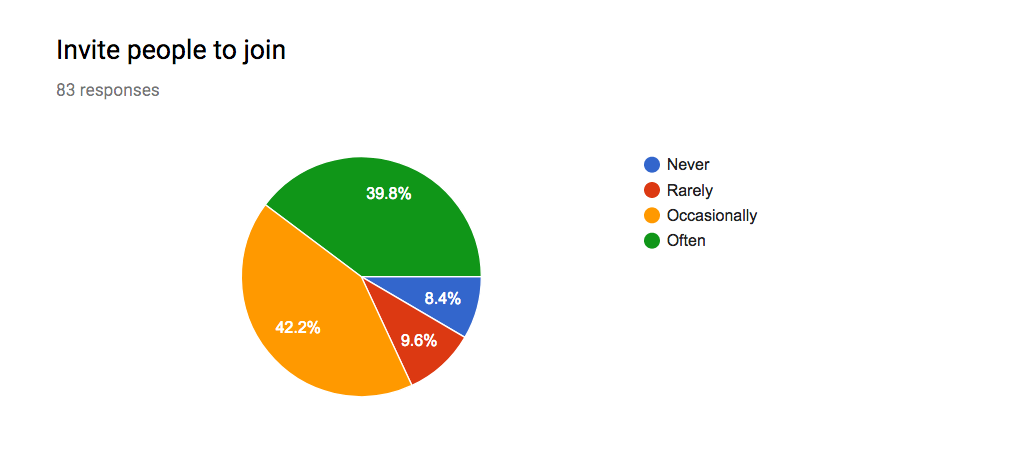

Inviting people to join is practiced by almost all respondents. 68 out of 83 have answered “often” or “occasionally”.

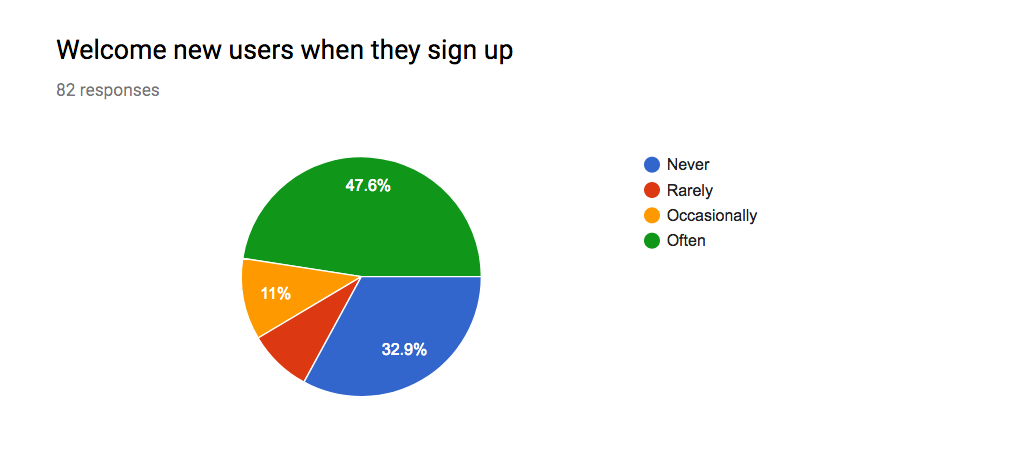

Once users sign up, most respondents send out a welcome message. 47 do it “often”, and a further 9 do it “occasionally”.

Engagement with users is overwhelmingly practiced. Only 5 out the 83 respondents do it “rarely” or “never”.

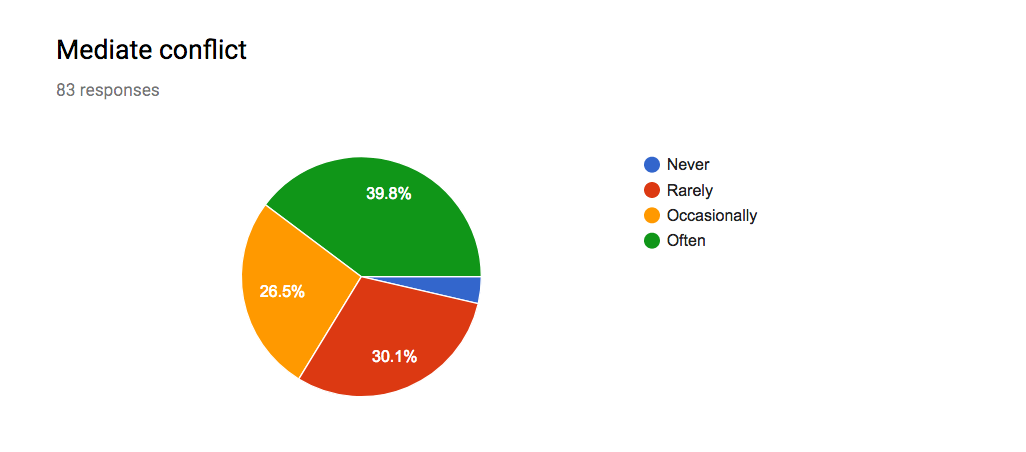

Conflict mediation is also an important activity. 33 respondents report practicing it “often”, and an additional 22 “occasionally”. Only 28 of them report peaceful communities, where conflict mediation is practiced only rarely or never by community managers. This was a surprise for me. I guess I gravitate towards in unusually peaceful online hangouts!

Almost every respondent engages in design or co-design of interfaces. Clearly community managers think doing so is part of their role.

Almost every one of them is also preoccupied with getting people to talk more to each other.

About nine respondents out of ten allocate at least some time to organizing offline community events, but only 12 of them reported doing it “often”.

Thanking and acknowledging active members is perhaps the most widespread activity, with over 90% of respondents engaging in it “often” or “occasionally”.

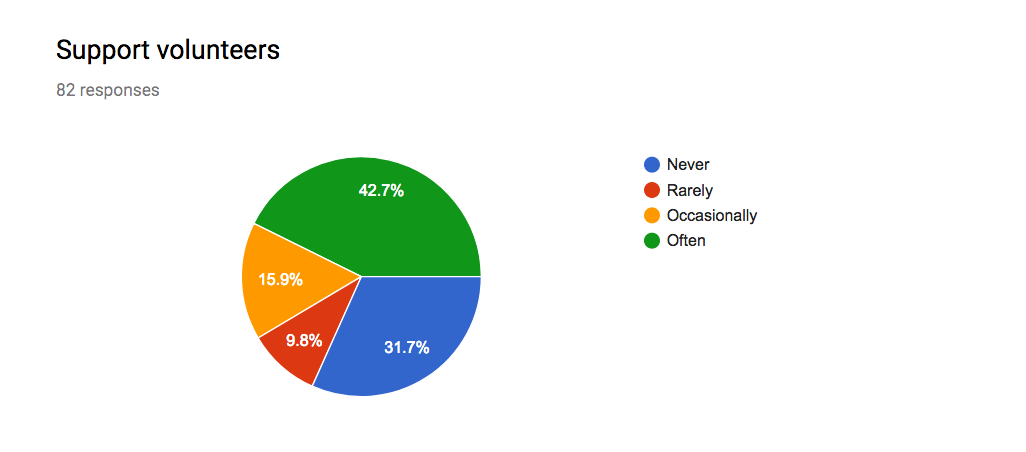

Finally, about half of the informants support volunteers “often” or “occasionally”. About a third never does it.

Most of the informants referred to rather established communities with over five years of history. Only 8 of them reported managing new community, created less than a year before taking the questionnaire.

The respondents were quite well distributed by size of the communities they manage. Interestingly, the relative majority manage large ones, with over 100,000 accounts each.

You can download the dataset from zenodo.org: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1210789. The data are open, published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license. This means you are welcome to use them for your own research, as long as you cite me as the dataset author.

Full references for the list of practices

Ganley, Dale, and Cliff Lampe. “The ties that bind: Social network principles in online communities.” Decision Support Systems 47.3 (2009): 266-274.

Iriberri, Alicia, and Gondy Leroy. “A life-cycle perspective on online community success.” ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 41.2 (2009): 11.

Kim, Amy Jo. Community building on the web: Secret strategies for successful online communities. Peachpit Press, 2000.

Kraut, Robert E., et al. Building successful online communities: Evidence-based social design. Mit Press, 2012.

Ludford, Pamela J., et al. “Think different: increasing online community participation using uniqueness and group dissimilarity.” Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems. ACM, 2004.

Panzarasa, Pietro, Tore Opsahl, and Kathleen M. Carley. “Patterns and dynamics of users’ behavior and interaction: Network analysis of an online community.” Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 60.5 (2009): 911-932.

Williams, Ruth L., and Joseph Cothrel. “Four smart ways to run online communities.” MIT Sloan Management Review 41.4 (2000): 81.

Young, Colleen. “Community management that works: how to build and sustain a thriving online health community.” Journal of medical Internet research 15.6 (2013).