2019: we are in trouble…

The 2019 European elections are going to be more relevant than usual. I will almost certainly lose them – and, if you are reading this, chances are you will, too.

I am a proud European. I take joy and pride in being a member of a polity engineered to prevent war by deep integration between historical enemies; the largest-ever polity based on rules, human rights and renouncing violence as a way to solve conflicts. Its emphasis on culture and diversity and tolerance, its focus on the individual’s well-being (as opposed to the “nation’s destiny” or other buzzwords beloved by autocrats and oligarchs) is humanity’s best shot at building a society where we can all flourish and take care of each other, best exemplified for me by Iain Banks’ Culture novels. The European edifice is likely the single most important positive contribution we, who live here, are ever going to be able to make. I am never going to give up on it.

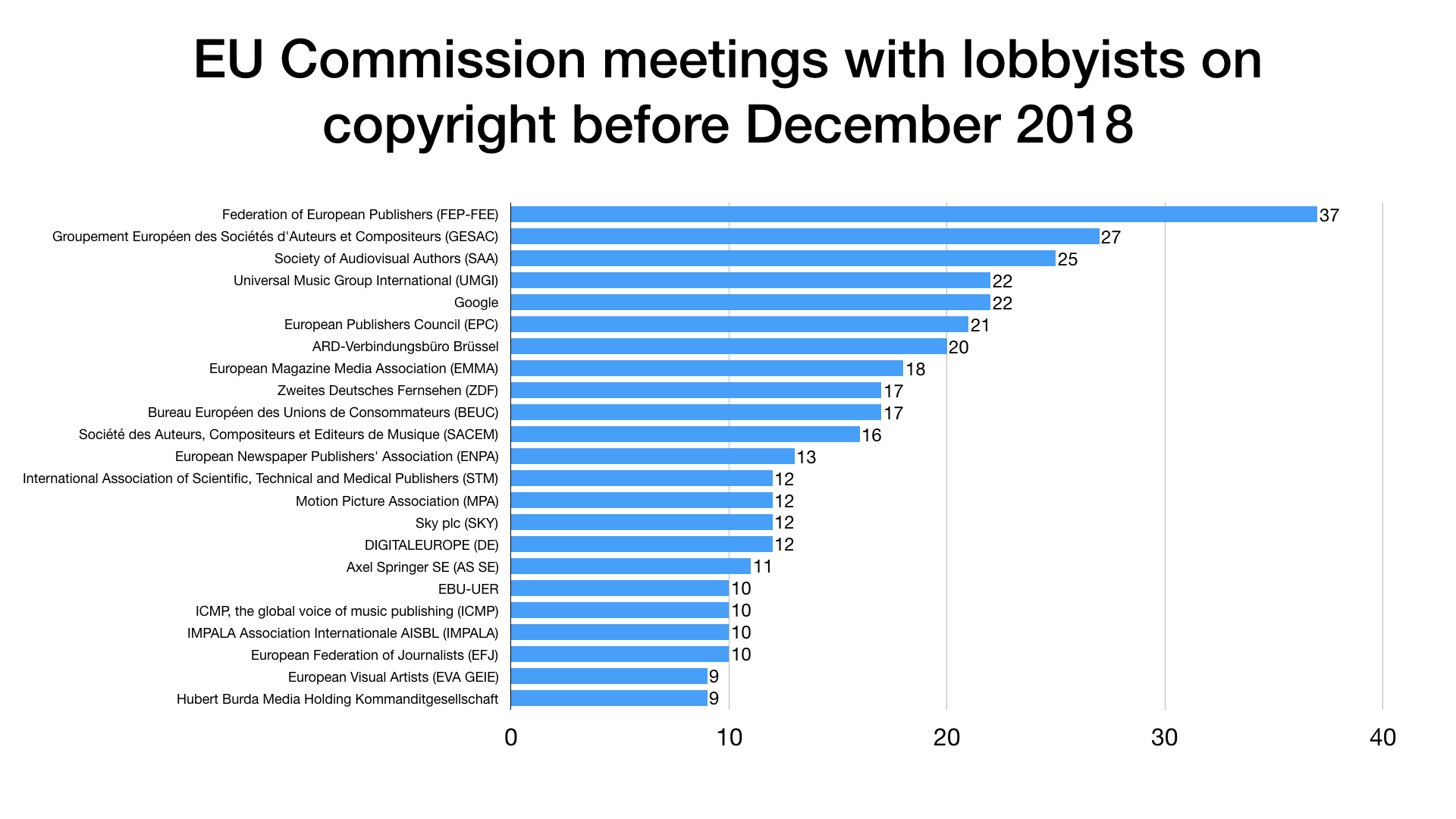

But with all that, Europe is still broken, and needs fixing. It has a structural democratic deficit, and it cannot be fixed without making the EU institutions directly accountable to its citizens, which means sidestepping member states. It has a culture of over-representation of certain stakeholders at the expense of others. And don’t get me started on the Euro, which cannot work without a fiscal union and a banking union, and we all know it, and we all have known it since its introduction was first seriously discussed, in the early 1990s (just ask Paul Krugman).

None of this is new. Here’s what is new, though: so far, we could just wait around. Maybe Europe will fix itself, we thought. Maybe we will have better ideas in five or ten years. The technocrats reassured us: yes, we are aware of the problems, but we are fixing them. Things used to get better, slowly but surely, every year. Look, more countries are joining! Look, we’ve abolished roaming charges for mobile phones! We have made it easier for you to study abroad!

But not anymore. Europe is in trouble. With Eurosceptic, populist parties coming to power in many EU countries, the technocrats can no longer guarantee the slow-but-sure progress of the European dream. Paradoxically, this is a sign of the EU’s success: it is now too important to have major flaws. We need to fix it, or we risk losing it altogether.

Here’s the thing, though. The next European elections are coming up in May 2019, and the populists look set to dominate the political debate. They have shadowy spin doctors like Cambridge Analytica, dark money from the American rights, troll armies roaming your social media (and Facebook, which looks more and more like a global social problem). In a few years, every party will have those; but right now, the far right has the advantage.

What I would like to do, and why

This is bad news, but it has a major silver lining: we can simply assume that, no matter what we do or don’t do, the 2019 European elections are lost to people like me. What this means:

- There is nothing to be gained from compromise “to build a broader anti-populist coalition”. No sense in giving up on our principles and ambitions if we are going to be defeated anyway. We will not ease up on human rights of migrants, or decarbonization, or anything at all just “because the people won’t understand”. This is about what is right, not what is sellable.

- There is nothing to be gained from slogan hustling and simplification. It’s not like I enjoy the intricacies of managing high-debt economies or integrating refugees flows. Some problems are complex. We refuse to dumb them down into nonsense; honor knowledge, domain expertise and technical skills in whoever possesses them and uses them to look for collective solutions; and wear words like “intellectual” or “technician” like badges of honor.

- There is nothing to be gained from engaging in shouting matches with trolls, bots and assorted idiots on Facebook. Why would we? We already know we are off sync with the Zeitgeist, we would not convince anyone.

All this, friends, means we are free. Once you take away compromise, dumbing down for “communication” and social media nonsense, what’s left is time to work, with people we love and respect, and a wonderful peace. We can use this peace to, finally, build stuff.

What stuff? I have no doubt people will come up all sort of things to do, and they will be brilliant. Alberto believes in teaching ordinary people to lobby the EU. Costanza wants to help activists access the little-know political channels to effect change at the European level. Debbie mounted a European Citizen Initiative to make your EU citizenship independent of your country’s decision to leave the EU. Me, I want to figure out a vision of Europe that is both beautiful and just, and achievable in the medium term (let’s say ten years). A Europe that, at some point in the future, might inspire people to get out and build it together. A Europe that presents itself as alternative to the petty version seen in action during the post-2008 financial crisis, which I associate to former German finance minister Wolfgang Schäuble and former Eurogroup president Jeroen Dijsselbloem.

It should be strongly idealistic and ambitious, but not a mere book of dreams. It is essential that we see a path from here to there. I have come to the conclusion that “there is no other way” is almost always false: policy makers armed with good will, technical skills and determination can achieve substantial change. You can probably think of a brave mayor or minister who inspired you and gave you hope with bold, compassionate action. I am currently intrigued by Abiy Ahmed, the serving Ethiopian prime minister. During his time in office, he ended a 30-plus year war with Eritrea; pardoned and released over 7,000 political prisoners; re-organized security forces to ensure respect of human rights; started liberalization of several sectors; and announced constitutional reform to move past the country’s present system of ethnic federalism, seen as divisive. He’s done all this in six months, even finding the time to broker peace talks between the South Sudanese government and rebellion. If he can do all this, why can’t we?

How this would work, and how you can be part of it

I would like to do this as follows.

- A European policy road map. A “book of dreams” is not good enough. To be truly inspiring, a vision for Europe should be actionable. And this, in government, means a policy road map: trade, research, finance, environment, migration… what gets done, and how that makes the world and our lives better. This provides for concreteness of the final output.

- A wiki. Open to contributions without permission by anyone who respects the (strict) rules for contributing. This allows our work to take advantage whatever people are willing to contribute: if there are a lot of people passionate about environmental policies, those policies will be very detailed and cross-checked. If only a few people care about research policy, that policy will be relatively coarse-grained.

- Apolitical and open sourced. The vision for Europe is based on values, not on political affiliation. Any party or individual leader can adopt, in part or as a whole, as part of their agenda, without our permission. This is reflected in the license used for the content.

- Structured as a citizens’ Multiannual Financial Framework. The MFF is a framework for the EU’s annual budget. It covers a period of seven years, and is approved by the European Parliament. So, it’s both long term and directly connected to the European elections. Reporting our vision to the MFF makes sure we do not propose unrealistic measures.

- Based on a thorough, granular understanding of the legal and administrative structure underpinning EU policy. Lofty goals are important, but they are not enough. Effective policy makers need mastery of the nuts and bolts of how the state’s (or, in this case, the union’s) machinery works. Great policy makers are hackers, squeezing extra performance out of the system in pursuit of their goals. I aspire to the level of mastery demonstrated by Yanis Varoufakis, Stuart Holland and James Galbraith in their Modest proposal for resolving the Eurozone crisis. What I like about it is that its solutions do not require major system reform, but can be implemented within the given legal framework: it is elegant and economical.

Granted, this is hard work. But it has several advantages:

- We do what we do best. If you are a policy nerd, the normal channels of public discourse do not give you much of an opportunity to contribute, because they tend to dumb down and oversimplify matters, in the interests of inclusivity (or in those of commercial communication). This way, we build a channel for people like you to deploy on Battlefield Europe, in a position where you can really shine.

- Good crowd, good fun. If you are like me, you are wary of speaking out in public, especially on social media. Discussing with people who do not respect or enjoy facts-grounded rational arguments is as pleasant or productive as playing chess with a pigeon. But we lay down the rules, and run our wiki out of our own server. No pigeons in this space. People can disagree (in fact they should), but not on fundamental values and especially not on standards for collaboration. We reserve the right to kick anyone right out if they are in breach: we are court, judge and executioner.

- Reuses what works. Some countries, many of which European, have had amazing policy successes. Portugal’s decriminalization of drugs and Finland’s radical education reform come to mind. Some of these successes, I’ll bet, can be “dragged and dropped” from one country to another. Others can’t, but still Europe could play a role in encouraging member states to adapt them to their needs.

- Builds a global network of hands-on policy experts. Doing this stuff will inevitably call for bringing in the people with the deepest thinking and broadest experience on the relevant topics. I already quoted Varoufakis’s remarkable work on debt restructuring from a Greek perspective; other of my personal favorites are former Romanian health minister Vlad Voicolescu, innovation economist Mariana Mazzucato and Italy’s former regional cohesion minister Fabrizio Barca (full disclosure: I consider him a personal friend). Chances are you have your own favorites, and you are welcome to involve them. By contributing to a common vision for Europe, these people will have a shared experience of collaboration; this will be, I think, the most important legacy of the initiative I am proposing here. This global, diverse group of people will be a sort of avatar of the élites I dream of for Europe: not shadowy foreigners, but normal, intelligent, generous, imperfect people who are also Greeks, or Danes, or Czechs, just like the rest of us, and who are happy to work together across state borders.

I think I have a pretty good idea of how these things can be achieved (read: attempted with integrity, knowing they can still fail even if you do everything right). I am thinking of putting together a small (minimum 3-4 people) group to coordinate all this. “Coordinate” means setting up and running the online space, welcoming people, smoothing feathers as needed, and generally assuming responsibility for moving it forwards. I will, however, not do it alone, as I have a life and political commitment can only be a small part of it. Would you consider being a part of this group? If so, let’s get together privately and manage expectations before we launch ourselves into it. No commitment implied for now.

EDIT – After seeking counsel from some wise friends, I have decided NOT to lead this at the present time. I would still be up for participating in it, or for making it a part of some larger, more structured effort.

Photo credit: Giampaolo Macorig on Flickr.com