My native country, Italy, is currently going through a crisis related to a ship called Sea-Watch-3. Owned by a German NGO, it rescued 42 migrants from the Mediterranean; was denied authorization to dock in the Italian island of Lampedusa; but docked anyway on humanitarian grounds. Its captain was arrested. As I write, it is unclear how it will end (here is the Guardian). Whatever happens next, I fear it will affect not just its protagonists (the 42 migrants, the captain, the Italian authorities and the latter’s political leaders), but all Italians. Those effects will be strongly negative. They could even disintegrate Italy’s sentiment of national unity.

Let me explain. Italians are human beings, and like all humans prone to overheating during discussions. To overstep the limits of civility, and cross from discussion into fighting. That’s normal. Just step into an Italian café on a Monday, and watch people discuss the Sunday’s football matches. It is very common to overhear people accuse each other of “stealing a victory”, or even “buying off the referee”. Of course, the actual people in those discussion were not even within a hundred kilometer radius from the stadium. Their accusers know this well, but they associate the opposite team’s supporters to the alleged wrongdoings of the team’s players or management. Humans are good at factionalism: pitting “you” against “us”, according to biologists, is innate in homo sapiens.

Something similar happens in the Sea-Watch 3 discussion. Many limits of civility and courtesy have been overstepped. I hope I am wrong, but I see the country resolving into two opposite factions of supporters. The stadium where the actual match is being fought is near-empty, but Italy’s bars are full of people shouting not only at the players, but at each other. I am reading heavy, heavy words: “kill them”, “sink them”, “inhuman” and so on.

Unfortunately, I predict the echo of these words will be with us for a long time. This has something to do with the Internet.

On the one hand, the Internet provides us with an archive of everything we share: the joy and the anger, the measured arguments and the insults and venting. It never forgets. If you, today, use the Net to demand that the navy sinks a ship full of unfortunate people, or to call minister X or representative Y a Nazi, you leave a digital trace that will not go away easily, or at all. Even if you repent, that post, or that tweet, will hang from your neck like the albatross from the neck of Coleridge’s Old Mariner.

On the other hand, social media tend to push us into “consensus bubbles” where most people are close to our own position. According to Zeynep Tufekci, these bubbles are not static, but carry us towards more and more extreme positions with time and the consumption of social media.

Together, these two effects create a situation where our most extreme positions become a cage that we can no longer break free of. If we change our minds, we know that someone will always be able to rub them in our face. And, once we express them, we find ourselves part of a bubble that rewards us for taking them: admires us, respects us as someone who is not afraid to “tell it like it is”. In this situation, it is hard to change your opinion.

Conclusions. In the age of social media, when a faultline forms in a community it tends to grow wider, crystallize, become irreversible. Forgiveness and reconciliation become harder. This is my reading of what happened in the UK: in 2015, the words “Leaver” and “Remainer” did not exist. In 2016 they were shorthand for “someone who votes Leave/Remain in the EU referendum”. In 2019 they are identities: go to any dating website, it’s full of people saying “I could never date a Leaver/Remainer”. Now, these identities are completely artificial, but the combined effect of unerasable records and consensus bubbles makes them effective anyway. I fear that, with Sea-Watch 3, we Italians have found our own faultline, our own Brexit.

In the short run, as the British example shows, it is likely that we will get mired into a continuous conflict that will cripple our ability to develop the country. After the referendum, the British government has done practically no new policy, not even around leaving the EU. And in the long run? No one knows. I fear that a deeply divided national community is unviable.

So what next? My opinion does not matter. If it did, I would use it to ask my countrymen to be compassionate, not (only) with the migrants on the Sea-Watch 3, but with each other. A person can, in a moment of frustration, get carried away and say something horrible without being a horrible person. The “enemy” that torments us on Twitter is just another human being, with a family, a car insurance to pay, maybe a dog. A couple of layers beneath his offensive language there might be arguments worth discussing.

No one has a monopoly on Italian-ness. But I like to remember this: after the fall of the fascist regime and the end of World War II, Italy gave itself a national unity government. Its minister if justice was communist leader Palmiro Togliatti, himself exiled during fascism. His most significant policy was a general amnesty. rolled out as an emergency measure, before Italy even had a constitution or a parliament. Wikipedia notes:

it pardoned and reduced sentences for Italian Fascists and Partisans alike. The amnesty included common crimes as well as political ones committed during World War II. In practice however, Fascists and collaborators benefited far more from the amnesty than Partisans did.

This move had far-reaching implications. Those who had been complicit in involving Italy in a war, and collaborated with an invading force, got home free, just like those who had fought against these choices. Fair? No. And indeed, Togliatti paid a high price to the backlash, also within his own party. But the government, and Togliatti himself, decided that reconciliation and mutual forgiveness were the only path towards a reasonably cohesive, stable nation. Conflict happens, but to move forward together reconciliation is necessary. Italy is a republic based on that reconciliation, and I do not think it has a future if we we won’t be able to reverse this trend towards entrenched positions and mutual, public insult. I hope we realize this, before it is too late.

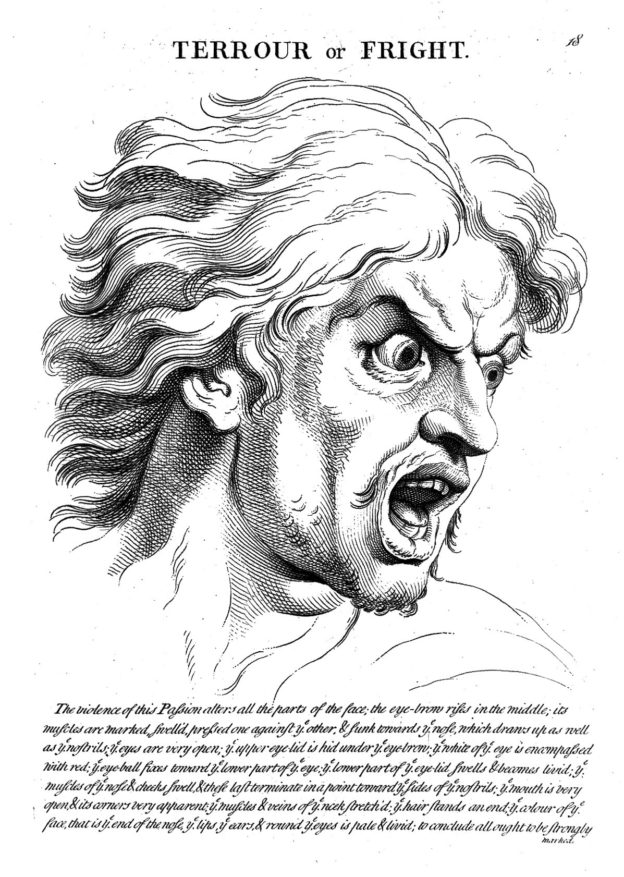

Image: Terrour with fright” from le Brun. Credit: Wellcome Collection. CC BY